Available documents

Exhibition

Collection, détournement, and recycling are central to the practice of a number of contemporary artists. By using natural objects mixed with more modern materials or manufactured products, all fabricate in their own way a universe populated by hybrid forms that tends, against all expectation, towards energy and equilibrium. Within this artistic “family group”, Vincent Ganivet and Séverine Hubard, brought together for this exhibition at the Grand Café, stand out for the particular interest that they take in materials and in the logics of construction.

With the adventurous trajectories that they follow, they take the vocabulary and syntax of the specialist and deregulate it, playing around with scale and space. Making a deliberately elementary use of technology, they leave room for the improvisation and ingenuity of the bricoleur. This allows them to create ephemeral spaces within practices that resemble vast open-ended construction sites.

Séverine Hubard

The gestures of assemblage, collage, accumulation and displacement in Séverine Hubard’s art originate in actions of construction. In a continuous link with the context in which she intervenes, the artist often concretises her interventions in the form of ephemeral structures made of recuperated materials. An ebullient researcher, the artist chooses materials that refer to her favourite hunting grounds of towns and the materiality of their buildings: offcuts from a DIY shop, broken windows or doors from condemned blocks.

The artist delivers herself to a pursuit of raw materials that celebrates the pleasure of the find. As the real substance of the work, these materials have a trophy value. The found object, repeated and accumulated, becomes a reserve that when worked on forms a landscape that is both familiar and unexpected, in which the simple gestures of the artist always remain readable. From this material diversity emanates a frank energy doubled with a direct poetry: as a rebellious bricoleuse, Séverine Hubard manages to invent a primitive vocabulary that best expresses the spirit of towns and of the peri-urban zones she has a particular feel for.

A lighthouse-metaphor, a bird on the lookout, a rhizome of pipework invading the exhibition space and setting up new circulations within it: Séverine Hubard’s proposal for the Grand Café draws on its Saint-Nazaire context to evoke a spontaneous archeology of the industrial present. The aesthetic is brutal and child-like at the same time, abolishing all separation between art and everyday life. It is a playful and abundant installation that is as much like a labyrinth as a fluid factory or a giant chessboard with oversized pawns, like Alice through the looking glass….

Séverine Hubard often seems to meet the burlesque universe of Jacques Tati (Playtime or Mon oncle) and the popular architecture of “Learning from Las Vegas” by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour – a key work for the artist. “Thirty years after their book appeared, their methods seem still topical to me: for an architect, studying the existing landscape is a way of being revolutionary, not in the too obvious way that would involve destroying Paris and starting again, as Le Corbusier suggested around 1920, but in a more tolerant way: questioning our manner of looking at what is around us.”

Equally, Séverine Hubard’s art contains in filigree a critical dimension that addresses our ways of perceiving a site: with fantasy as a weapon, it traces the contours of a quietly subversive universe without planning permissions.

Vincent Ganivet

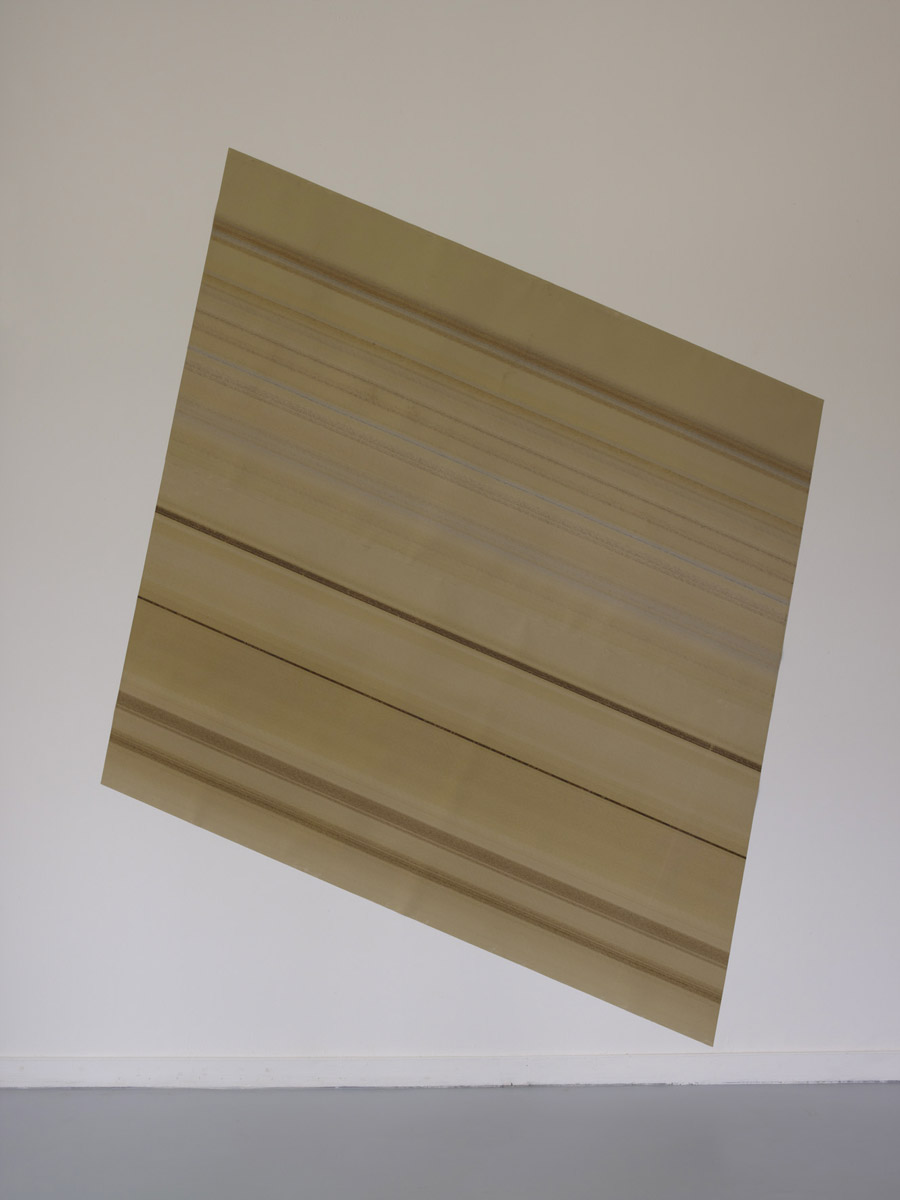

For a decade, Vincent Ganivet has been obstinately and acutely deploying strategies that divert the everyday. Beginning with an elementary material vocabulary, his overall policy is that of counter-employment: in his hands rubble becomes landscape material, he exhibits water damage, dust forms constellations, fireworks go off in broad daylight and breeze block arches fly away. The artist developed a taste for simple and modest materials from his experience on building sites: his works make the universe of the construction industry (its raw elements, weight-bearing function) converge with modular games (assembly, stacking, tension and balance) and with the constant urge to go further.

The transcendence of physical constraints is particularly felt in the Caténaires [Catenaries] series, vertiginous blocks that he develops with an extreme concentration on the gesture. So that these self-supporting arches hold firm, Vincent Ganivet goes back to the catenary formula, an equation traditionally used by Gaudí, and allies it to age-old building techniques (the arch, leverage and drystone) in the intuitive way of a DIY enthusiast excited by mechanical forces.

To push the system as far as he can, the artist is always raising his trajectories higher, twisting them or taking them to their precarious limits: in 2011, at the Karlsruhe Kunsthalle, a sculpture with five supports and a keystone collapsed during the exhibition. Although he includes failure as an integral part of his research, Vincent Ganivet nevertheless prefers to walk on the edge of the precipice rather than experience the fall, and to continue defying the laws of gravity using just naked materials with finesse and without trickery.

For the Grand Café, the artist is showing the piece Caténaires vrillés [Spiral Catenaries], two self-supporting arches whose slender aerial curves cross themselves in torsion. A reflection on space and its perception, a dialogue with the history of architecture: above all the sculpture fascinates by its dialectical dynamic (stable/unstable, massive/streamlined, vulgar/refined) and the way it captures the space around it and puts it under tension.

As a formal counterpoint and echoing its curves, the artist is reactivating Ronds de fumée [Smoke Rings], a processual work from 2008 adapted to the space. Using everyday circular recipients, Vincent Ganivet stifles the emanations of flares against the wall of the gallery. As combustion and as chromatic projection, the process connotes both pyrotechnic accidents and popular ceremonies. The Smoke Rings fresco of burnt confetti condenses well the spirit of the work: the impact of a gesture, inventive, and marvellous.

Éva Prouteau